High density or sustainability?

Increasing grove density is not at odds with sustainability guidelines. This is evidenced by observations and estimates of environmental impact carried out in superintensive groves in Puglia, Italy.

Super-intensive cultivation is now the only method for cultivating olives that makes it possible to keep the costs of producing extra virgin oil well below the wholesale price, and represents the result of international scientific and technological know-how in the field of olive growing.

Super-intensive farming is present alongside the traditional and intensive systems in countries with a long tradition of cultivation such as Italy and Spain, bringing a breath of fresh air to a long-suffering production sector, and, above all, improving profit margins for olive growers. Wholesale extra virgin olive oil prices above 5-6 euro / kg represented a flash in the pan, as expected, and today prices are once more quoted at levels of around 3-4 euro/kg at most.

International research has validated the agronomic and economic sustainability of super-intensive groves. Like other fruit tree species, managing the cultivation of the olive grove (of any olive grove) requires technical knowledge and professional experience, specific to the growing environment.

Research is rapidly proving fruitful, including with regard to the ecological sustainability of super-intensive olive groves, also known as “very high density groves”. This article illustrates and highlights various aspects which are crucial to the environmental sustainability of super-intensive olive groves.

Scientific evidence and direct field experience can resolve some queries – queries that are no doubt prompted by legitimate concerns, but also those involving unsubstantiated accusations, sometimes resulting from an ideological, ignorant or biased approach which is now, fortunately, increasingly rare.

Our testing, over a period of almost twenty years, has shown that the super-intensive olive grove requires the same level of agronomic contributions as any other olive grove in the same area, with the same level of production, and that its management entails the knowledge and application of the Code of Good Agricultural Practices referred to in the Ministerial Decree of April 19th 1999 (published in OJ no. 102 OS no. 86 of May 4th 1999) and the Integrated Production Regulations updated annually by the regions and published on their institutional websites.

Management of super-intensive olive groves

Seasonal irrigation volumes vary notoriously according to annual temperatures and rainfall, and the properties of the soil on the farm. For a super-intensive plant it can exceed 2,000 cubic meters per hectare in dry years; however, irrigation volumes are usually below this figure.

Recent research conducted in Sicily, in environments where much moisture is lost to evaporation, has shown that 1,300 cubic meters per hectare would be sufficient to meet the annual water needs of super-intensive olive plantations.

Fertilizer doses are a function of the expected production levels, which normally exceed 12 tons of olives per hectare, and would normally entail ordinary values of 130 units of nitrogen, 30 of phosphorus and 110 of potassium.

Phytosanitary management, carried out according to the updated Guidelines for Environmentally Sustainable Defense/Integrated Defense Regulations, allows for a maximum of 2-3 copper treatments, permissible in organic farming, and 2-3 insecticidal treatments, carried out according to the principles of guided control, and always adapted for a particular year’s climatic profile.

Soil management in super-intensive plantations is carried out according to criteria of environmental sustainability/integrated management, and takes into account the contributions of fertilizers and organic supplements, green manure, controlled inter-row plant cover (photo 1), shredding of the pruning waste in situ and mulching of rows with biodegradable materials without the need for chemical weed control. From the fourth year after planting, the conversion of super-intensive olive groves into organic plantations is now a widespread reality.

Natura 2000 bioindicators

The agronomic techniques employed in super-intensive olive groves increase their environmental sustainability to such an extent that they favor, rather than hinder, the creation of habitats which support the life cycle of plant and animal species present in special protection areas and sites of community interest, as per the Natura 2000 form, and which represent specific bioindicators of natural areas.

In late spring, beneath the rows of a mature super-intensive olive grove, the flowering of regional wild orchids belonging to the genus Serapias was observed in the Murgia region of Bari (photo 2). These orchids have an entomophilic pollination system, and, in natural ecosystems, are found in arid and uncultivated meadows, scrubland and forest clearings. The presence of such plant species has been observed for two consecutive years.

Super-intensive olive agrosystems, managed according to the environmentally sustainable criteria previously exposed, neither pollute the environment nor harm pollinating insects; rather, they enable the formation and stabilization of habitats suitable for delicate and ecologically demanding plant species.

Fruit bodies of basidiomycete fungi belonging to the genus Coprinus, known bioindicators of the absence of heavy metal pollution, have been observed on rows of super-intensive olive groves mulched with organic materials (photo 3).

Treetops favourable to bird life

Animal species are also found among the scientific evidence. Nests attributable to the Sardinian Warbler (Sylvia melanocephala) have been photographed in the same plantation (coincidence?) for several consecutive years, within the particularly dense vegetation of the varieties adapted to the super-intensive system (Photo 4).

The Sardinian Warbler generally lives in the Mediterranean scrub, characterized by dense and low bushes, and is also found in forest environments that present a lush shrubby layer. The emergence of a habitat suitable for the nesting of this bird in the super-intensive olive grove has been promoted not only by the vegetative characteristics of the cultivars, but above all by the manner of farming and the pruning criteria applied by such plantations.

Indeed, formation around a central axis gives rise to a ‘full ‘ structure in the tree, while the avoidance of any pruning of the interior of the fruiting branches promotes the formation of a low and uniformly dense crown.

In addition, this bird’s most common prey include a variety of species of insects, aphids, crickets and moth larvae, along with spiders, none of which are lacking in the super-intensive olive grove. The availability of such a food source is therefore a further indicator of a rich and balanced insect population. Moreover, in late summer and autumn the Sardinian Warbler also eats the fruits and seeds of numerous plants, and we can’t rule out the fact that it may also have taken advantage of olives.

Carbon and water footprint

The traditional and unirrigated cultivation of the olive tree is known for being a fairly passive crop system from an economic point of view. And from an ecological point of view?

When measuring the environmental impact of any production process, including an agricultural one, with advanced synthetic indicators such as its carbon footprint (CF) and water footprint (WF), the numerical results can often be surprising.

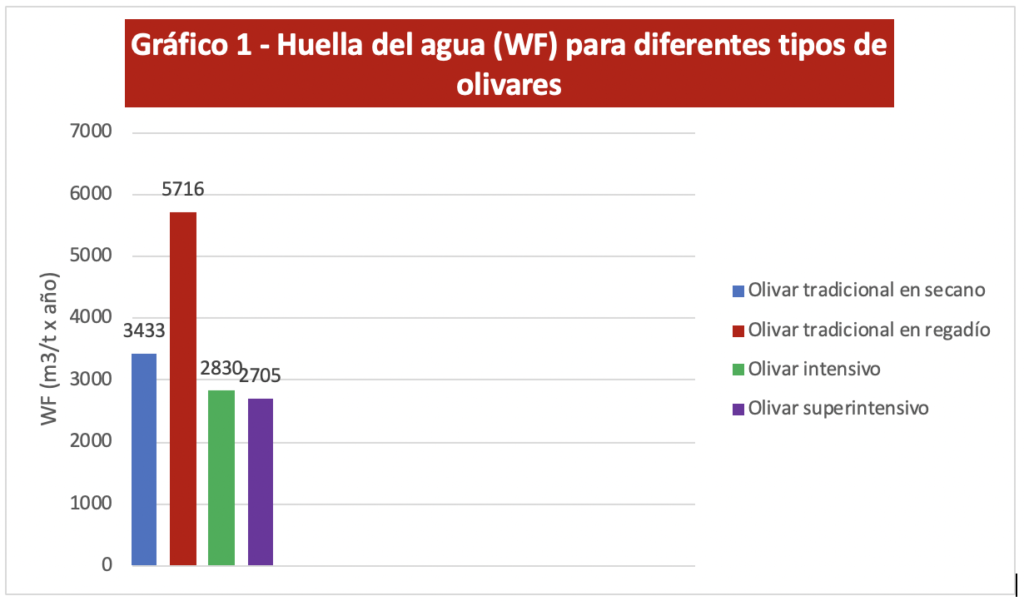

Diagram 1 – Water footprint (WF) for different types of olive grove

Traditional irrigated olive grove

Intensive olive grove

Superintensive olive grove

It has been shown that the intensive cultivation of olive trees using irrigation can as much as double the amount of greenhouse gases which are immobilized in plant biomass and soil (carbon sinks) compared to traditional unirrigated cultivation. On the other hand, both the increasing scarcity of fresh water and the important role it plays in agri-food production underline the urgent need to optimize the use of water in human activities and, in particular, in agriculture.

Indeed, agricultural activities and agro-industry can consume as much as 70% of the fresh water available worldwide; in Italy, the percentage is lower than this, at around 30% of the total, which nevertheless corresponds to a substantial amount (approximately 15 billion cubic meters per year) and is concentrated in two highly agricultural areas: the Po valley and Puglia (FAO data).

In this context, the water footprint is able to correctly quantify both the consumption and pollution of fresh water by a production activity.

Efficient use of water resources

Estimating the WF enables the necessary impact mitigation measures to be put in place and thus facilitates a more sustainable use of the precious non-renewable natural resource. Recent studies have shown that the WF of super-intensive olive groves is comparable to that of irrigated intensive olive groves, estimated at around 2,700-2,800 cubic meters per ton of olives produced per year.

A traditional unirrigated olive grove, in the same soil and climatic situations, has an higher water footprint, measured at around 3,400 cubic meters per ton of olives per year, linked to less efficient fertilizer use in dryland farming.

The situation worsens if we perform this ‘irrigation conversion’ on traditional olive groves: their WF rises to 5,700 cubic meters per ton of olives per year, due to an increase in production which is proportionally inferior to the input of available water resources. In other words, it seems that watering a traditional olive grove results in a waste of fresh water!

More modern crop systems, on the other hand, have a lower demand for fresh water from irrigation. In fact, the largest component of the WF is the ‘blue quota’ – that linked to irrigation – which represents almost 77% of the total for traditional and intensive irrigation systems, as opposed to 74% for superintensive ones.

Understanding of the WF could contribute to better transparency and understanding around the final product, providing consumers with a tool to assist in making well-informed decisions. These results, together with those that are being highlighted by the estimate of the CF of olive groves and oil, could also be useful in promoting and improving olive cultivation in the context of eco-sustainable agriculture and agro-industry.

Last but not least is the hillside protection that super-intensive groves can offer, if we take into account the fact that the soil area covered, and therefore protected, by traditional groves is at most 50%, whereas in super-intensive olive groves it exceeds 60%. If then we consider that the ‘spare’ surface area of these latter groves is filled with controlled plant cover, it is not hard to understand the valuable contribution that super-intensive olive cultivation can make to the fight against hydro-geological instability in hilly areas, as is being demonstrated in the south of Spain.

Sustainability and quality

The super-intensive olive growing system has numerous and considerable requirements in terms of ecological sustainability, resulting from the cultivation techniques that characterize it: planting distances and cultivars, along with management of the canopy, soil, water and nutrients.

The established and lasting presence of plant and animal species of community interest constitutes the most immediate and eloquent response on the possible environmental impacts deriving from the realization of a super-intensive olive grove, including for agricultural areas in sites of community interest and special protection areas.

Paradoxically, it is the high tree density which represents the essential reason for the environmental sustainability of this crop system. In addition, the agronomic result of the super-intensive olive groves is a high quality product, sometimes even organic, at low production cost. Perhaps we should rename super-intensive olive groves as super-sustainable olive groves!

This information, combined with other key aspects, such as economic and social considerations, could provide a starting point for the formulation of guidelines for both the rational management of the olive grove and for regional, national and community agricultural policies.