Xylella: An Increasingly Complex Picture

In Puglia, the pauca strain has reached south of Bari, and new subspecies are emerging, including fastidiosa, which has been found on grapevine and reported in Spain and Portugal.

The Beginning and Development of the Epidemic

It has now been 12 years since it was discovered that the bacterium Xylella fastidiosa subsp. pauca was the cause of the massive die-off of olive trees in Salento, the southern part of the Puglia region.

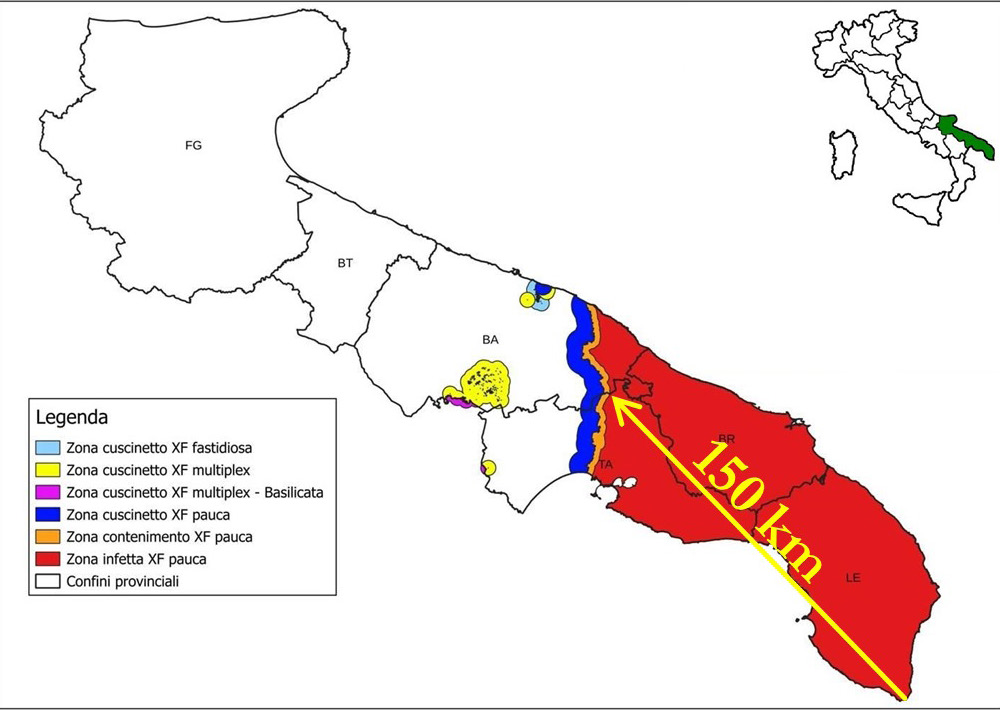

The first outbreaks, initially very localized, quickly spread northward in an epidemic pattern, affecting the entire provinces of Lecce and Brindisi, most of Taranto, and even appearing in some municipalities in Bari province. Today, the infected area covers about 8,000 km²—40% of the entire region—where more than 10 million olive trees have died.

This catastrophic scenario was fueled by a “perfect storm” of factors that no one in the industry could have foreseen:

The bacterial strain ST53, highly aggressive and lethal to olive trees; The near-exclusive presence of two traditional cultivars—Ogliarola Salentina and Cellina di Nardò—both highly susceptible; Abundant populations of the insect vector, the spittlebug (Philaenus spumarius); Climatic conditions favorable to both the bacterium and the vector’s life cycle, which remains on olive trees for extended periods.

Spittlebugs, along with leafhoppers, began to pose a phytosanitary threat in southern Italy in the late 1990s, as organophosphate insecticides were banned and changing climate conditions favored their spread.

From the original outbreak site, the latest infected olive trees are now about 150 km away.

A New Scenario for Olive Growing

It has now been 12 years since it was discovered that the bacterium Xylella fastidiosa subsp. pauca was the cause of the massive die-off of olive trees in Salento, the southern part of the Puglia region.

The first outbreaks, initially very localized, quickly spread northward in an epidemic pattern, affecting the entire provinces of Lecce and Brindisi, most of Taranto, and even appearing in some municipalities in Bari province. Today, the infected area covers about 8,000 km²—40% of the entire region—where more than 10 million olive trees have died.

In recent years, the northward advance of the infection front has slowed, as has disease progression in infected trees in Salento. This slowdown is due to:

- Less favorable climatic conditions for bacterial development;

- Different cropping systems, with other species and soil management practices;

- Implementation of legally mandated containment measures;

- Lower vector populations.

These measures include:

- Soil tillage (plowing, harrowing, shredding) to control juvenile stages of the spittlebug before they move to plants;

- Chemical treatments against adult vectors from April/May to October, as indicated by the regional monitoring plan;

- Uprooting all plants within a 50-meter radius of any infected tree.

Disease progression in infected trees has also slowed because the inoculum reservoir has greatly diminished due to tree mortality and the removal of severely damaged groves, often replaced with resistant cultivars (lower bacterial load and colonization). This has significantly reduced the percentage of infected spittlebugs and their ability to transmit the bacterium over time—a key factor in rapid decline and tree death.

Meanwhile, alongside the first two resistant varieties—FS17 and Leccino—two more cultivars showing resistance or tolerance have been authorized for planting: Leccio del Corno and Lecciana.

What “Resistance” Really Means

Resistance does not mean immunity. Key traits of a resistant cultivar:

- Does it get infected? Yes.

- Infection → symptoms: longer incubation period.

- Milder, more limited dieback symptoms on the canopy.

- Lower bacterial concentration in the plant.

- Limited bacterial spread within the plant.

This means spittlebugs have fewer chances to acquire and transmit the bacterium, reducing inoculum pressure in the environment.

Currently, the northernmost presence of the bacterium involves a few olive trees (seven, promptly eradicated as of late March 2025) on the southern outskirts of Bari. These were isolated trees near major roads and roundabouts, likely infected by “hitchhiking” vectors transported passively by vehicles from infected zones.

Meanwhile, olive regeneration continues in Salento, with hundreds of hectares replanted with resistant varieties.

The Current State of the Epidemic

The monitoring program in Puglia has carried out over 1 million tests in 10 years. New investigative methods have been tested, such as monitoring insect vectors in buffer and disease-free zones to anticipate bacterial spread.

In 2024, an unexpected and alarming discovery occurred: two additional subspecies were found in Bari province—fastidiosa (genotype ST1), the notorious causal agent of Pierce’s disease in grapevine, and multiplex (genotype ST26) on the Murge plateau.

The greatest concern is the detection of X. fastidiosa subsp. fastidiosa in a small area adjacent to Europe’s most important table grape-growing district southeast of Bari (Noicattaro, Rutigliano).

So far, nearly 50,000 tests in this restricted area have identified ST1 on almond (214 plants) and grapevine (127), as well as cherry (7) and Polygala (1). Total eradication is underway, including the removal of about 30 hectares of vineyards, with the hope of completely eliminating the outbreak.

For now, one certainty remains: the Pierce’s disease vectors present in California (sharpshooters) are absent here, and our spittlebug is considered only a secondary vector for that disease.

The multiplex outbreak on the Murge plateau, with over 40,000 samples tested in cereal and pasture areas, involves scattered almond trees, often growing on traditional dry-stone walls.

The full database from the extensive monitoring program conducted in the Puglia region is available on the official website www.emergenzaxylella.it. The database is accompanied by a note from the Regional Phytosanitary Observatory, providing essential guidelines for proper interpretation.

It is an enormous amount of data—over one million analyses—unrepeatable and unsustainable in other contexts, yet it has allowed a comprehensive picture of the bacterium’s presence in the region and how to plan future responses to devastating phytosanitary emergencies.

Considerations

One might think that Xylella is now everywhere. If territories were subjected to such extensive and meticulous monitoring, reports in Europe—and beyond—would certainly increase. This leads to the conclusion that if you look for it, you will find it!

In reality, the issue is far more complex and nuanced, with technical and scientific aspects that sometimes diverge from the approach taken by legislators and the administrations enforcing regulations.

Xylella fastidiosa includes very different variants, with diverse host species and pathogenicity, resulting in varying risks for different crops. These variants are grouped genetically into subspecies (in Europe we have pauca, fastidiosa, and multiplex), which in turn include different genotypes that may have significant biological differences.

The agent of olive quick decline, subspecies pauca, has several genotypes grouped into two categories:

- “Coffee” strains, capable of infecting coffee and olive but not citrus;

- “Citrus” strains, capable of infecting citrus but not coffee or olive.

In Europe, only “coffee” strains have been found so far, particularly the notorious ST53, which caused the massive olive tree die-off.

Unfortunately, the recent Implementing Regulation 2024/2507, while updating the list of plant species requiring traceability codes on plant passports and reducing the containment zone width from 5 to 2 kilometers, still enforces the same control measures as previous rules—issued when little was known about the bacterium in Europe—without distinguishing between genotypes or subspecies.

This disregards findings from major EU-funded research programs and annual monitoring by member states. Specifically, it ignores that:

- The bacterium, with its various subspecies, is far more widespread than assumed 10 years ago;

- Infection effects range from symptomless (latent) to mild symptoms, and only rarely to severe, destructive diseases. Fortunately, the most frequent cases appear to be latent or mild, while severe phytopathies occur only in rare epidemiological scenarios involving specific strain/susceptible species/vector/climate combinations;

- The first detection resulted from severe olive dieback symptoms that prompted investigation. Subsequent findings in France, Spain, Germany, Portugal, Italy, and the recent detection of subspecies fastidiosa in Valencia de Alcántara, Spain, mostly stem from monitoring activities rather than disease outbreaks—as noted, Xylella is found because it is sought;

- Multiplex is the most prevalent subspecies, associated with endemic spread;

- Subspecies pauca remains the most severe form detected;

- Severe Pierce’s disease symptoms in vineyards do not necessarily follow the establishment of subspecies fastidiosa, which, while present in several Mediterranean areas (Balearic Islands, Israel, Lebanon, Portugal, Puglia, and recently mainland Spain), has not triggered major PD outbreaks.

Another point to investigate: detections often occur first in almond or Mediterranean scrub species, and only later—once subspecies identification prompts targeted searches—in grapevine.

The ongoing monitoring in Puglia, with peaks of 250,000 samples tested annually and a major vector surveillance program, represents a globally unique plan—unsustainable long-term and not easily replicable elsewhere. However, it is invaluable for understanding the real presence and impact of Xylella under local conditions and for critically revising EU pathogen management regulations.

Given the high level of spread already confirmed in Europe—despite far less intensive monitoring than in Puglia—and the fact that most cases show mild effects, strict application of EU rules often risks causing more harm than the pathogen itself.

Consider, for example, the increasingly large areas affected by multiplex, where regulations mandate uprooting olive trees classified as “specified species,” despite no evidence that the strain present in Puglia (similar to Alicante province) can infect olive trees.

The hope is for a more realistic, pragmatic approach by EU authorities—a radical rethink of the Regulation—so containment strategies are not uniform regardless of subspecies or environmental and cropping conditions. Greater flexibility should allow National Plant Health Services to assess and decide case by case on the most appropriate, effective, and sustainable measures.

From an agronomic perspective, robust breeding programs by scientific institutions with diverse expertise are urgently needed to develop resistant germplasm to safeguard Mediterranean olive growing. This is the only viable path to face future phytosanitary emergencies (next alert: citrus greening) that threaten Mediterranean agriculture, traditions, landscapes, and ecosystems—essential to prevent another apocalypse like the one that struck Salento, once home to millennial olive trees that shaped human history.